57

56

M

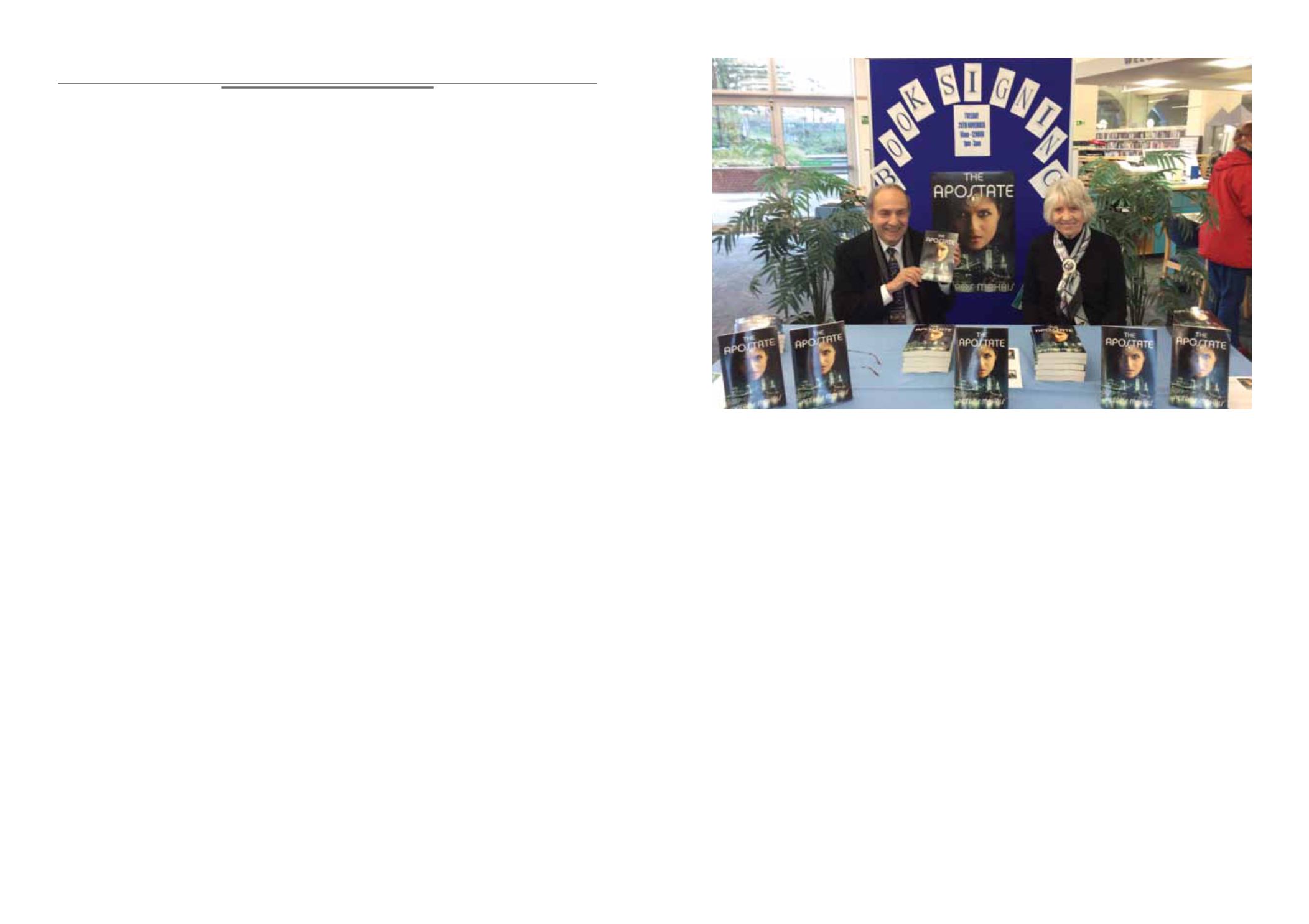

ember of the Greek Cypriot diaspora Petros

Hadjitofi Makris presented his first book,

The Apostate

, on 25 November 2014 at the Barry

Library in the UK.

A mystery thriller about greed, religion and sex,

all interwoven in murder and retribution about

contemporaryissues,theexpatriatedCypriotdescribes

his accomplishment as themost fulfilling yet.

Here, Petros Hadjitofi Makris takes us through the

long journey that brought him here.

Ashort biography

By Petros Hadjitofi Makris

Whenever I tell the story of how a

small donkey changed my life, nobody

believes me. I was born in 1935, in

Akaki, a small farming village west of

Nicosia; that’s where it happened.

Life was really hard then. There were

no tractors, combine harvesters, cars,

vans, or lorries, and because there was

no electricity, there were no mod cons

either. Consequently, all the domestic,

andfarmworkhad tobedonemanually.

Adults, and children after the age of

twelve, when they finished the elementary school,

worked in the fields from dawn to dusk to scrape a

living. Compulsory schooling ended at the age of

12 and hardly anybody went to a secondary school.

Apart from going to church on Sundays, there was

no time for hobbies, relaxation, and entertainment.

Toys, presents, birthday parties and pocket money

were unheard of. Most of the people were poor, very

poor. All their produce was for family consumption,

and those who had a little extra couldn’t sell it for

cash; barter was still widespread.

It didn’t take me long, at an early age, to realise that

that was a miserable existence, and I didn’t hesitate

to make my thoughts known to my parents. The

worst jobs on the farm were the harvesting of the

wheat and barley. Mind you, other manual farm

work was almost as bad; there was the picking of

the cotton from the plants, the gathering of beans

(broad beans, haricot beans and black eyed beans);

not forgetting the lentils, chick peas, sesame seeds,

cumin and coriander seeds. All these were done in

the soaring heat, the wind, and dust. My endurance

was often pushed to the limit, which was reflected

in my outbursts of verbal monologues, such as “I

hate this work”, “When I grow up I am going to go

to Australia (people used to immigrate to Australia

then) and never come back” or “This is the hell

the bible talks about.” To which my mother, who

was a devout Christian, bless her soul, would say,

“You mustn’t say that Petros; it is

blasphemy.”

Adifficult start in life

After the elementary school, I became,

not by choice, an apprentice to a

farmers’ carpenter (

aletraris

) in the

village.My father thought it was a good

job, because the farmers will always

want ploughs, donkey saddles to carry

the crops, and the like. After about a

year themaster carpenter toldmy father

that I didn’t have it in me to become a

carpenter, so I had to go. Other trades or professions

were unheard of then, so I ended up working in the

fields with my parents, brothers and sisters; that was

when things got worse for me.

Actually, when I think back aboutmy early life in the

village, I instantly recall three occasions in particular,

which overwhelmme with dread.

The first one was when I was about six and had to

do a man’s job, literally. At the time my village was

involved in a project of getting running water for

irrigation from a series of wells/shafts which were

linked at the bottomwith a tunnel. This is an ancient

system known as

qanats

. The wells are spaced

in a line about 20 to 30 metres apart in an easterly

direction and get progressively deeper. The soil

from the wells and tunnel is lifted up in a bucket and

The Apostate

A book by Petros Hadjitofi Makris

dumped around the well. The tunnel, which starts at

surface level as a trench (where the water is planned

to come out), is small; just big enough for the man

who is digging it. As I was small and not heavy, I

was lowered in a bucket into the last and deepest

well; I guess it was about 100 meters deep. Once at

the bottom of the well I had to unhook the bucket

and drag it along the tunnel to where the man was

digging and pushing the soil behind him, in order to

extend the tunnel. My job was to fill the bucket with

the excavated soil and drag it back to the well. I then

had to unhook the empty bucket, which would have

been lowered in the meantime, and hook the filled

one, which was then pulled up, and so on. Even for

a small child the working area was claustrophobic,

and it was dark, and wet; not a nice place to be and

work, and that’s putting it mildly!

Beware of the ‘asproyaouri’!

The second onewaswhen I was about thirteen. I had

to take our three laden donkeys with bales of wheat

from our field, which was a few miles away from

the village to our ‘

alonny

’ (threshing field), which

was near the house. We had a very large field there,

which incidentally is now occupied by the Turks,

and because it was far away, we had to sleep there

in the night in order to save the travelling time. Part

of my journey back to the field was at night, and as

there was no moonlight I could not see anything. So

I just sat on the donkey and let it carry on walking

with the other two following behind. As I was late

arriving, my fathermust have thought that I was lost;

led astray by the

‘asproyaoury’

– literally, thismeans

‘white donkey’. There was a myth in my village

about this; apparently, as I understood it, it was some

kind of spirit. According to my older brother you

could see it sometimes. It was a white shimmering

light which appeared suddenly on the tip of the

donkey’s ears and led you astray. Now thinking

about it, it must have been caused by static, if it did

exist. I must have been a mile or so from our field,

when I heard my father calling me; in the still of the

night sounds carry and you can hear for miles. I was

relieved; I was not led astray by the ‘

asproyaoury

’!

The third episode was when I went with my father

and our three donkeys to another field, some

distance from the village to bring back the dried up

broad bean stalks. Bundles of stalks were tied on

“Of all my

achievements,

whether they

were professional,

academic, or career

advancement, the

most fulfilling has

been the writing and

publication of

The Apostate

”

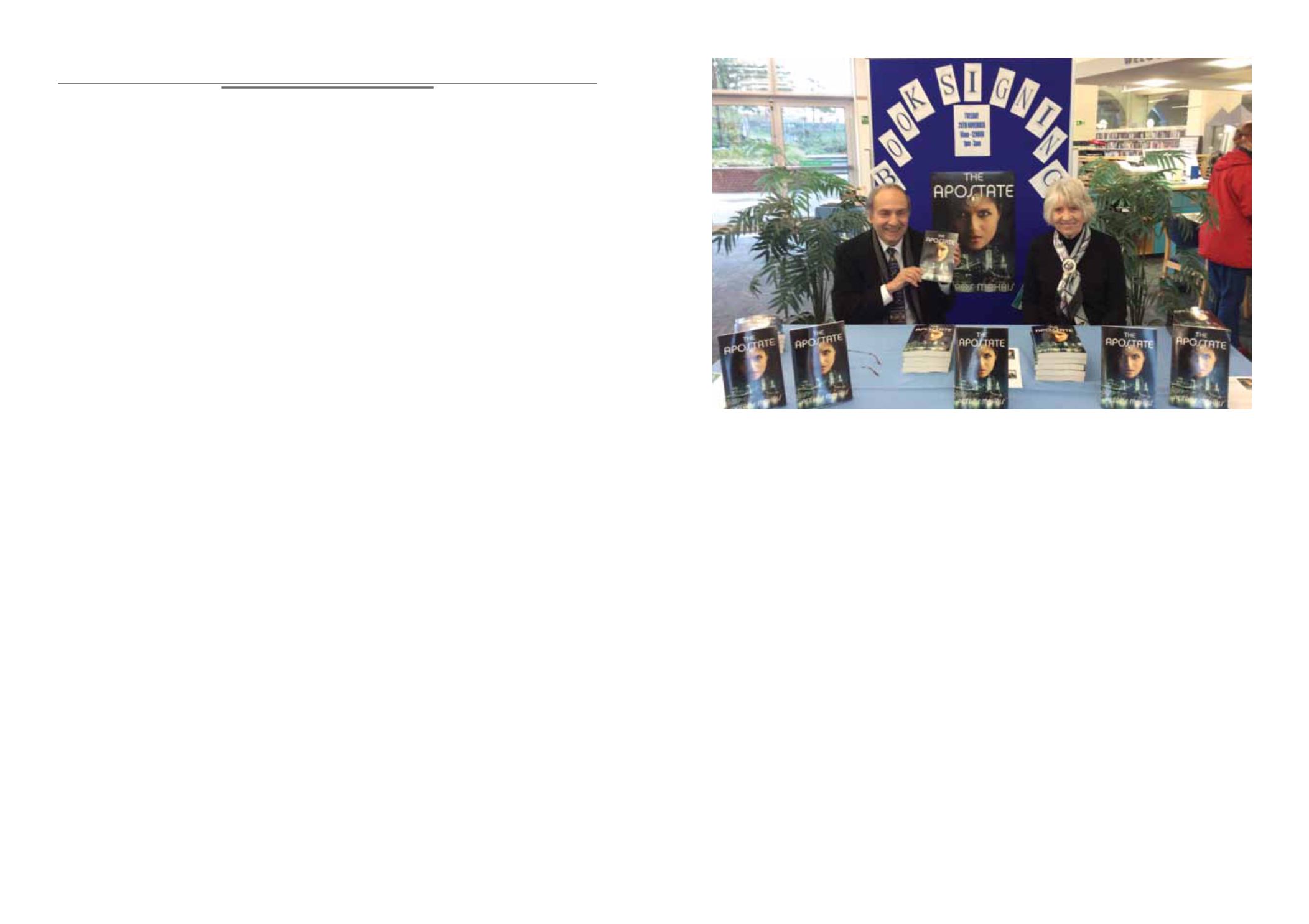

Dr Petros Hadjitofi Makris and Mrs Beryl Makris at the signing of his first book, The Apostate